Placenta praevia: Frequently asked questions

How is the diagnosis made?

The location of your placenta is identified at your mid-pregnancy anomaly ultrasound scan.

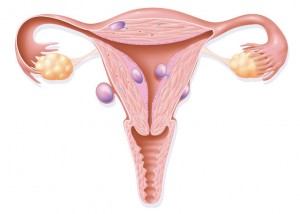

If the placenta is covering the neck of the womb it is termed a placenta praevia; if it is not covering the neck of the womb but is within 20mm of the neck of the womb it is called a low lying placenta.

The location of the placenta will be checked again closer to the end of the pregnancy, usually at around 36 weeks. 9 out of 10 women will not have a low lying placenta or placenta praevia at their follow up scan.

What does this mean?

For me

Having a low lying placenta or placenta praevia increases the chance of experiencing bleeding during pregnancy.

A planned caesarean birth will be recommended to all women with a low lying placenta or placenta praevia towards the end of pregnancy.

For my baby

If there is extremely heavy vaginal bleeding during pregnancy from a low lying placenta or placenta praevia, this may affect your baby’s wellbeing.

A baby may need to be born prematurely if a woman experiences extremely heavy vaginal bleeding during pregnancy.

If you experience any vaginal bleeding, contractions or pain you should attend hospital without delay.

What are the ‘red flag’ symptoms/concerns, which means that they should be reported immediately?

If you experience any vaginal bleeding, contractions or pain you should attend hospital without delay.

How may this impact my birth choices?

A planned caesarean birth will be recommended to all women with a low lying placenta or placenta praevia towards the end of pregnancy.

Heavy bleeding is possible during the caesarean birth, and this may require a blood transfusion and medications to limit the blood loss. Rarely, if there is no other way to control the bleeding, it may be necessary to remove your womb (hysterectomy) at the time of a caesarean birth for a low lying placenta or placenta praevia.

What will this mean for future pregnancies? How can I reduce my risk of this happening again?

A low lying placenta or placenta praevia is associated with previous caesarean birth, assisted reproductive technologies and smoking.

Supporting your partner during labour and birth can be a rewarding and bonding experience for both of you. Use the Personalised Birth Preferences plan in the app to help you think about both of your needs and choices for labour and birth.

Staying well-hydrated and nourished during the labour will help you to stay alert, so come prepared with non-perishable snacks and drinks. It is also okay to take a break occasionally, especially if labour is long. Chat about this with your partner before labour so everyone’s expectations can be met.

If you have helped to pack the hospital bag, you will know where to find a hat and nappy for your newborn baby, as these are the first things the midwife will ask you for.

Depending on hospital policy it may be possible to have more than one birth partner during labour. It is wise to check with your midwife ahead of time.

Supporting your partner during labour and birth can be a rewarding and bonding experience for both of you. Use the Personalised Birth Preferences plan in the app to help you think about both of your needs and choices for labour and birth.

Staying well-hydrated and nourished during the labour will help you to stay alert, so come prepared with non-perishable snacks and drinks. It is also okay to take a break occasionally, especially if labour is long. Chat about this with your partner before labour so everyone’s expectations can be met.

If you have helped to pack the hospital bag, you will know where to find a hat and nappy for your newborn baby, as these are the first things the midwife will ask you for.

Depending on hospital policy it may be possible to have more than one birth partner during labour. It is wise to check with your midwife ahead of time.